You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping When it works, writing is an act of alchemy. Ideas, emotions and slices of experience brew in a writer’s mind, sometimes for years. Then, by some happy catalyst or simple maturity, they coalesce into some shape and rhythm, some thing which you describe on the page in little black chains like long, complicated chemistry formulae. Okay, nice metaphor (for a student, anyway), but it doesn’t explain how said formula, or any story or line can hit you in the gut like absinthe, burning into your memory thereafter. Words alone aren’t enough, in the same way that throwing together a pot of hormones, proteins, water and an overpriced handbag will not result in your sister-in-law.

When it works, writing is an act of alchemy. Ideas, emotions and slices of experience brew in a writer’s mind, sometimes for years. Then, by some happy catalyst or simple maturity, they coalesce into some shape and rhythm, some thing which you describe on the page in little black chains like long, complicated chemistry formulae. Okay, nice metaphor (for a student, anyway), but it doesn’t explain how said formula, or any story or line can hit you in the gut like absinthe, burning into your memory thereafter. Words alone aren’t enough, in the same way that throwing together a pot of hormones, proteins, water and an overpriced handbag will not result in your sister-in-law.

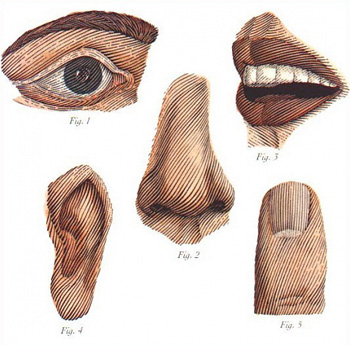

As a creative writing student, my main aim, of course, is to write. And I do. But I’m also taking this time to take a good long look at superb writing, to open it up and rummage around inside. I’m hoping to discover what I can about the sorts of materials and processes that make up a solid machine within which the “ghost” of great writing can happily haunt our hearts and lives. I know I won’t magically inhale the voice of Faulkner or the vision of Updike, but I might plunder a few choice ingredients for use in my own lab. This week, I’m looking at a few aspects of sensual description.

When I’m actually reading a good book, it’s the author’s ideas and observations that strike me most profoundly. But from a distance, long after I put it down, these blur into a general, inarticulate sense of “quality”, while what I actually remember are the colours, sounds or smells of particular scenes. I was completely engrossed and moved and humbled by Chris Cleave’s The Other Hand, its unflinching exploration of human rights abuses and what is at stake in asylum, as well as the limping hopes of family relationships. But what I remember most acutely is the mute girl in the lemon-yellow sari, the unbearable sounds of an act of violence. The senses seem to saturate the text deeper into your very being. There is a delightfully evocative passage in John Banville’s The Sea, where he discovers his first love in close-up through a mosaic of her smells, most of them not even very nice: of her faintly green teeth, unwashed crevices and fruity breath. His reverent description of her brilliantly evokes the pungency of small children and their heady vitality.

Dave Eggars is a master painter, using simple colours to bring ordinary scenes to life, making them so real the edges hurt. Take this description, from A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, of his mother in intensive care: “A light above her bed is kept on, creating a much-too-dramatic amber halo around her head. A machine behind her bed looks like an accordion, but it is light blue. It is vertical and stretches and compresses, making a sucking sound.” Somehow a “light-blue ventilator” is so much more heartbreaking than a “ventilator”. It puts me back into every hopeless hospital room I’ve ever been unable to avoid, reviving the smells, the banality of apparatus and its indifference to its host. Because even if I don’t know exactly what a ventilator looks like, I do know that innocuous “light-blue” colour of medical equipment and all it implies. Eggars continues, colouring in the tableau with sound: “There is that sound, and the sound of her breathing, and the humming from other machines, and the humming from the heater, and Toph’s breathing, close and constant. Mom’s breaths are desperate, irregular.” As we read, these brushstrokes act like parts of an orchestra tuning up, culminating in one, quiet sombre chord in our mind.

Colour can also reek of emotion and memory, just like smell. In 1970s America, the discount chain K-Mart’s logo was a washed out shade of turquoise. Where I grew up, K-Mart stood for everything that was not cool, and the risk of anyone knowing your clothes came from there was terrifying, when your mother’s purse hovered in such proximity to its airy, strip-lit abyss. I am still repelled by anything in “K-Mart blue”, my stomach churning with unease. Eggars gets this. “Beside the TV there are various pictures of us children, including one featuring me, Bill, and Beth, all under seven, in an orange dinghy, all expressions panicked.” That orange—the colour of smelly, faded life-jackets I associate with ill-advised, inexpert but desperately optimistic family sailing expeditions. I remember the awkwardness, the uncertainty, the pressure to have a “good time” as a family. Ugh. All that from the flash of orange in the middle of that sentence. And he knows it, continuing, “It is the picture we know best, the one we have seen every day, and its colors—the blue of Lake Michigan, the orange of the dinghy, our tan skin and blond hair—are the colors we associate with our childhoods.”

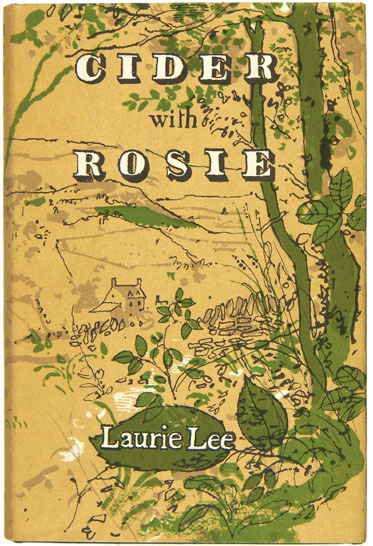

At the moment I am discovering Laurie Lee, and rushing off alternately to write myself, or top myself, he is so devastatingly inspiring. Every paragraph is a kaleidoscope of experience, bringing me so deeply inside his perception that I can almost feel his heart beat inside me. At the start of Cider with Rosie, he is a three-year-old who’s been dumped in the long grass while his family unpacks at their new country cottage: “A tropic heat oozed up from the ground, rank with sharp odours of roots and nettles. Snow-clouds of elder-blossom banked in the sky, showering upon me the fumes and flakes of their sweet and giddy suffocation. High overhead ran frenzied larks, screaming, as though the sky were tearing apart.” Sight, sound and smell, all imploding in tight-chested panic. As the family raced around him discovering their new habitat, “The sisters spent the light of that first day stripping the fruit bushes in the garden. The currants were at their prime, clusters of red, black, and yellow berries all tangled up with wild roses… I sat on the floor on a raft of muddles and gazed through the green window which was full of the rising garden. I saw the long black stockings of the girls, gaping with white flesh, kicking among the currant bushes. Every so often one of them would dart into the kitchen, cram my great mouth with handfuls of squashed berries, and run out again.” By this time our thinking is so colourised that we ourselves supply the swashes of dripping purple berry juice all over the girls’ fingers and his eager mouth. Granted, Laurie Lee was a poet, too, so not doubt he had pockets full of these sparklings. But the colours he uses here are simple: red, black, yellow, green, white. Not subtle, sophisticated or contrived. Fresh and clear, landing a direct hit.

It is often said that the job of the poet is not to tell you what she felt, but to recreate the event or experience as closely as possible so that you feel what she did. How else do we experience the world but through our eyes, ears, nose, tongue and skin? And how richly, and alive?

Click to read parts two and three of this feature.

About Emily Cleaver

Emily Cleaver is Litro's Online Editor. She is passionate about short stories and writes, reads and reviews them. Her own stories have been published in the London Lies anthology from Arachne Press, Paraxis, .Cent, The Mechanics’ Institute Review, One Eye Grey, and Smoke magazines, performed to audiences at Liars League, Stand Up Tragedy, WritLOUD, Tales of the Decongested and Spark London and broadcasted on Resonance FM and Pagan Radio. As a former manager of one of London’s oldest second-hand bookshops, she also blogs about old and obscure books. You can read her tiny true dramas about working in a secondhand bookshop at smallplays.com and see more of her writing at emilycleaver.net.

‘Airy, strip-lit abyss’ – nice. A sensual piece about the sensual tool kit of a writer.

Great piece, this! I know exactly what you mean. Great writing really does change you.