You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

‘Excuse me. Does this train go to Ames?’ Taeko Endo asked a woman reading a newspaper in one of the seats near the door.

‘Yes, it does,’ the woman answered, smiling.

Taeko thanked her and took the seat across the aisle. She put down her bag of presents and the flowers she’d bought inside the station and relaxed. She was on her way to visit Edward Hunt. He’d been her English teacher at the junior college in Tokyo and she’d been secretly in love with him ever since. [private]Two years earlier, the year she’d graduated, he’d returned to Massachusetts; now she was there to get her bachelor’s degree and to see if she could make him fall in love with her.

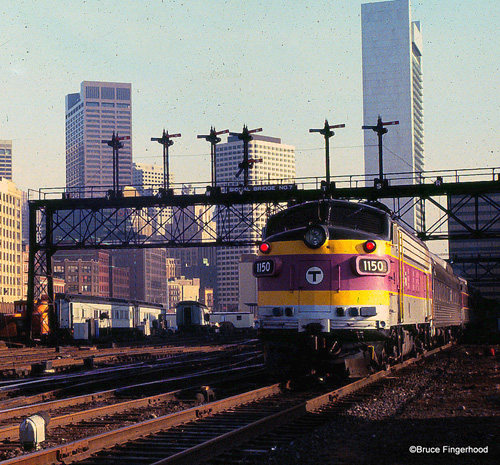

She looked out the window at the people passing on the platform. A few minutes later the conductor came into the car and called out something she couldn’t understand. The train started moving. Collecting the fares, the conductor made his way down the aisle toward her.

‘A round trip ticket to Ames,’ she said when he reached her.

‘That’ll be ten dollars.’

She gave him the money. He clipped a piece of blue paper and handed it to her.

‘Excuse me. What time will the train reach Ames?’

‘You don’t like to keep him waiting?’

He said this in a loud voice and the people sitting nearby laughed. It took Taeko a few seconds to get the meaning. She was finding her English was better than she’d expected but she had trouble telling when people were joking. The conductor winked at her and looked at his watch.

‘We’re running a little late, so about one-forty.’

‘Thank you.’

‘You’re welcome.’

The train slowed. The conductor announced the next station but she couldn’t understand him. The train entered a tunnel and stopped. A dozen or so people came into the car. The train started again and in a few moments it picked up speed. Taeko looked out the window. It was cloudy now; it had been sunny when she’d left the dormitory. The train passed through what she guessed was the outskirts of Boston. There were vacant lots, rundown buildings with broken windows, rusting cars with the engine or a tire missing. The train was moving fast. They went through a residential section. The houses were big but not well-kept. On many the paint had faded or peeled and there were broken fences and unmowed lawns. Children played in the yards and streets. A man smoked a cigarette in front of one of the houses. His hair was long, like Edward’s had been, and she wondered for the umpteenth time if Edward had a girlfriend. He might even be married. She’d known of no girlfriend in Japan. He was thirty years old. In Japan, if a man was thirty and unmarried, people thought there was something wrong with him. The conductor came into the car and announced the next stop.

No one from her car got off. Three people boarded and the train started moving. She looked at her watch. It was one-twenty. At the next station the woman across the aisle stood. She smiled at Taeko as she passed. In a moment the train started moving.

As the train got further from Boston, the neighborhoods improved, but they still disappointed her. She’d expected more from America. Ever since she was a little girl she’d dreamed of visiting there. The sun came out again. It was after one-thirty and she worried about missing her stop. The train had stopped twice since the woman had gotten off. At the last station half of the passengers in the car had departed. The conductor came into the car and announced the next stop. Taeko couldn’t catch the name but she knew it wasn’t Ames. He walked down to her and leaned over.

‘The next stop after this one is yours.’

He was gone before she could thank him. She drew the bag with the presents for Edward closer and gripped the handle. The train slowed and then stopped at the next station. No one got on or off. The train pulled out of the station and two minutes later the conductor announced Ames. Taeko stood, picked up her flowers and walked to the end of the car. The train stopped moving and Taeko pulled open the door. The conductor was already on the platform. He held her arm as she came down the steep steps.

‘Thank you,’ she said, smiling and bowing.

‘Tell him it was the train’s fault, not yours.’

He was up the steps by the time she figured out what he meant. She smiled and bowed again, but he wasn’t looking her way. She had to stop bowing; it wasn’t an American custom. She walked out through the parking lot to the street. From her bag she took the pocket map she’d purchased in Boston and found the page for Ames. The Hunts lived on Sycamore Street, which was off the street running in front of the station. She counted the side streets. Sycamore should be the third one.

She walked up the sidewalk, past a used car lot and a service station. The temperature had gone down in the last hour and the rain felt of air. Ahead on the right was a McDonald’s. The houses along the road were small and in poor condition. She was disappointed again. Edward had said Ames was one of the best towns in America. There was a sign for Sycamore at the corner and she turned left. She had no idea how far up the street Edward’s house was. She didn’t even know if he lived there. All she had was the address he’d given his students before leaving Japan. During the past two years she’d sent him numerous cards and letters. He’d sent her one Christmas card a year and a half earlier. When she’d arrived in Boston, she’d tried, with the help of her roommate, to look up his telephone number in the phone book. The number wasn’t listed.

Taeko could see shops ahead of her. On the right was a nearly empty parking lot. On the next block was a small park. The grass was short and green. She stopped at a red light at what seemed to be the center of town. There were stores up and down both sides of the street. Few of the stores looked open. A group of teenagers stood on the sidewalk. The light changed and she continued up Sycamore. There were more stores, another parking lot and then only houses. The yards were wide and well-kept; the houses, neat and set back from the road. Tall trees lined both sides of the road. This was her image of America.

She had been checking the house numbers. Edward’s was one-thirty-two. The numbers were in the fifties now and suddenly she was nervous. The street darkened as thick clouds moved overhead. A man and a woman holding hands walked down the other side of the street. Taeko crossed a side street. The house on the left was number eighty-four. All of the possibilities she had been mulling all week – Edward wouldn’t be home; Edward didn’t live there; Edward was married; and, worst of all, they had nothing to say to each other – were suddenly real. She crossed another side street. The numbers were in the hundreds now. Clutching the presents and flowers, she continued walking. She passed one-twenty-six, one-twenty-eight and one-thirty. Then she was standing in front of one-thirty-two. The house was brick. Along the front was a row of bushes. She went up the walk, made of different colored slabs of stone. Through the open window next to the door she could hear a television or a radio. Hunt was engraved in gold on the black mailbox. She took a deep breath and rang the doorbell. A tall, blond woman opened the door. Except for her glasses and her age, she looked just like Edward. She had to be his mother.

‘Hello.’

‘Good afternoon. Are you Mrs. Hunt?’

‘I am.’

‘My name is Taeko Endo. I was a student of Edward’s in Japan.’

The woman’s face showed no understanding. Then she smiled and opened the door.

‘You’re one of Sachi’s friends. Didn’t they tell you, honey? They’re in New York now. They moved when Eddie got the job at the college.’

‘New York?’

‘Long Island, actually. You didn’t come all the way from Japan to see Sachi, did you?’

Taeko shook her head.

‘Well, that’s good. Did you come in from Boston?’

‘Yes.’

‘Well, come in. There’s no sense in standing outside. It’s going to rain, anyways.’

Taeko looked up at the dark sky.

‘Sachi and Eddie will be very sorry they missed you.’

Taeko stepped into the hall.

‘Come in here. I was just watching a movie. It’s no good, anyways. Tom – he’s my husband – is playing golf with his friends. I don’t know what they are going to do when the rain starts. I told him this morning it was going to rain but he never listens. Just sit down anywhere and make yourself at home. I’ll get you some coffee or would you like something else?’

Taeko shook her head.

‘Coffee is okay then?’

‘Yes, please.’

Mrs. Hunt went out of the room. Taeko put her bags on the floor and sat in one of the armchairs. All of the lights were on. The furniture was old. On the wall above the television there were several photographs.

Mrs. Hunt came back carrying a tray with two cups of coffee and two pieces of apple pie.

‘Here you go. I made this apple pie this morning and it’s still fresh. Sit over here. It’s easier to eat.’

She placed the tray on the coffee table. Taeko moved to the chair at the end of the table. Mrs. Hunt sat on the sofa.

‘Sachi and Eddie didn’t know you were coming?’

‘No.’

‘Well, that’s good. Those two have a tendency to forget. I was talking to Eddie last night and he didn’t say anything.’

She picked up the apple pie and the coffee and placed them in front of Taeko.

‘Thank you.’

‘Are you staying in Boston now?’

‘Yes.’

‘And are you working?’

‘No, I’m a student.’

‘Which school are you going to?’

‘Boston University.’

‘Well, that’s a very good school. One of Eddie’s cousins went there. When Sachi first came out here, she went to UMass for a while. What are you studying?’

‘Business, I hope. I’m taking some English classes this semester.’

‘What do you need to study English for? Your English is excellent.’

‘No. I can’t speak English well.’

‘I tell you it’s a lot better than Sachi’s when she first came out here. Tom and I didn’t know what to think when Eddie came back from Japan with her. At first, Eddie had to translate everything. Her English is very good now, mind you. She’s a lovely girl. Just like a daughter.’

Mrs. Hunt stopped talking to eat some pie.

‘Are you staying in the dorm?’ she asked after a moment.

‘Yes.’

‘Well, that’s convenient. And how did you get out here? I didn’t see a car.’

‘I took a train.’

‘That’s good. Help yourself. Don’t be shy.’

She motioned to the piece of pie in front of Taeko. Taeko took her first bite. It was very good.

‘How long have you been out here?’ Mrs. Hunt asked.

‘A week.’

‘A week and you know your way around well enough to come all the way out to Ames.’

‘The pie is delicious.’

‘Thank you. Tom loves apple pie. Eddie, too, for that matter.’

Taeko took another bite.

‘What did you say your name was, honey? I’m sorry. I’m terrible at names, especially foreign ones.’

‘Taeko Endo,’ Taeko said slowly.

‘You’ll have to write it down. I’ll tell Sachi the next time I’m talking to them. I’d call now but I know they’re not home. They said they were going to the beach today. Then again, it might be raining in New York already.’

‘Let me get that address for you,’ she said, standing.

She looked out the window.

‘The rain hasn’t started yet.’

She left the room. Taeko took another bite of the pie. She was feeling bold and she stood and crossed the room to look at the photographs. On top there was a faded one of a soldier. Below it was one of Edward when he was a child and one of when he was in high school. He hadn’t changed much over the years. There was a little girl. She must be Edward’s sister although Taeko had never heard him mention any sister. Then Taeko saw the wedding picture. She leaned forward. It was several seconds before she recognized the bride. It was Sachiko Nakano. She’d been in Taeko’s class at the junior college but Taeko hadn’t known her well. Taeko heard Mrs. Hunt’s footsteps. She came into the room with a piece of paper.

‘Would you like to see the wedding pictures? I have some upstairs somewhere. I’d have to look for them.’

She came over to where Taeko was standing.

‘Who’s the little girl?’ Taeko asked on impulse.

‘That was Kathy, Edward’s little sister. She died of leukemia when she was ten. Cancer.’

‘I’m sorry to hear that.’

‘Well, it was a long, long time ago.’

‘Sit down and finish your pie,’ she said. ‘I made a copy of that address for you.’

‘Do you mind if I use the bathroom?’

‘Go ahead, honey. It’s on the right as you go out the door.’

Taeko stayed talking with Mrs. Hunt for nearly an hour. It was just three o’clock when she got up to leave. Mrs. Hunt wanted her to stay until it was time for the train but Taeko told her she wanted to look around the town.

‘It was very nice talking to you,’ Mrs. Hunt said at the door. ‘I get lonely in the afternoons. Make sure you get in touch with Sachi and Eddie and we’ll have you over for a good American dinner the next time they’re down. And thank you for the flowers. They’re lovely.’

‘You’re welcome. And thank you very much for the apple pie and coffee.’

‘You’re welcome. Tom would run you into Boston if he were home. But you never know what time he’ll get back from golf. They like to have a few drinks afterwards. I don’t drive myself.’

‘Thank you. Goodbye.’

Taeko went down the steps. At the end of the walk she turned and waved.

‘You’d better hurry if you want to beat the rain,’ Mrs. Hunt called.

Taeko started off. At the corner she looked back but Mrs. Hunt was gone. There was a breeze and she could smell the ocean. The clouds were black. She still had the bag of presents for Edward. She hadn’t known Sachiko Nakano well. She’d been one of the rich girls who’d dressed up every day and who’d had their own cars. She hadn’t seemed very serious about studying. She was beautiful, though. Tall with long legs. Her eyes were big, too. Not like a Japanese’s. At school there’d been a rumor she modeled. Taeko was glad Sachiko and Edward hadn’t been there. She wouldn’t have known what to say to Sachiko. And she might have thrown the piece of pie in Edward’s face. She’d take a pass on that good American dinner. She’d liked his mother, though.

At the town center Taeko stopped. The dark clouds made it seem much later than three o’clock. The same group of teenagers was there, or maybe it was a different group. A bookstore in the middle of the block was open and she walked down to it. She looked at the books for a few minutes. Before leaving, she found Newsweek in the magazine rack. In Japan she’d read it faithfully and she wanted to start again. She paid and went out. She continued down the street as far as the last store. Then she crossed and came up the other side. Only the ice cream parlor was open. One of the teenagers was leaning back against a car, eating an ice cream cone. Taeko was almost past the shop when she decided she wanted an ice cream. When she came out with it, she saw the first big drops of rain. They were coming down slowly and there was no need to hurry. She turned right at the corner. She couldn’t believe Edward had married Sachiko Nakano. Taeko had read him completely wrong. She wondered how long they’d been going out in Japan. He’d been their English teacher in both their first and second year. The rain was still coming down lightly when she reached the station. A girl was smoking on a bench. The smell made Taeko want a cigarette. She’d quit six months earlier. She walked out to the platform and looked at the rain coming down on the tracks. Deep down she’d known all along she had no chance. A fool’s errand was what they said in English. She’d been on a fool’s errand. She started crying.

The real rain started when she was on the train. The wind blew it against the window. All the way back, she stared out, thinking about Edward and Sachiko. Wet, the rundown buildings near Boston didn’t look so bad. This was the country she’d dreamed of visiting.[/private]

About N/A N/A

Tony Concannon grew up in Massachusetts. After graduating from college with a B.A. in English and American Literature, he taught in Japan for the next 18 years. Since returning to the United States, he has been working in human services. Stories of his have appeared in Thought Magazine, The Taproot Literary Review and Down in the Dirt.

Way to go, Tony! I blogged about your success and provided a link to this story.